The 60-Second Fix Side Plank Protocol

Imagine This

You’re queuing for a coffee, shifting your weight side to side.

A small fidget that seems harmless — until your back starts to ache.

That slow pull is what this side plank Warrnambool guide is all about. It’s a quiet signal from your body saying, “I’m tired of holding on.”

You’re not alone. Up to 70% of healthy adults develop back discomfort when standing still too long (Sorensen et al., 2015).

The difference between those who finish the day feeling fine and those who ache comes down to one thing: how their body shares the load.

Some people — what researchers call pain developers — brace and hold still, believing stillness equals stability.

Others keep a soft, natural sway — a quiet rhythm of micro-movements that help the body distribute effort (Gregory et al., 2008).

So that small fidget you do without thinking?

It’s not a bad habit.

It’s your body’s built-in protection system, keeping circulation flowing and load balanced.

When endurance fades, that rhythm disappears — and your back ends up doing overtime.

That moment in line isn’t weakness. It’s feedback.

And it’s your first clue that endurance — not just strength — keeps you steady for the long haul.

📌 KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Endurance beats strength.

- Pain doesn’t show up when you’re strong — it shows up when you’re tired. Building endurance in your core and hips keeps your back stable long after strength fades.

- The side-plank is your early warning system.

- If you can’t hold 60 seconds, you may have an endurance gap — meaning your hips and sides fatigue before your back, forcing it to do extra work.

- Small moves protect big structures.

- Gentle postural shifts — a foot on a rail, a knee bend, a weight change — restore blood flow and reduce spinal fatigue. Movement protects posture.

- Smart consistency wins.

- Five calm minutes a day with the McGill Big-3 builds quiet, lasting stability. Quality reps and regular resets beat occasional hard sessions every time.

Why Endurance Matters

We often talk about strength as if it’s the body’s main currency — push more, lift more, brace harder.

But in real life, pain rarely shows up when you’re strong — it shows up when you’re tired.

Practising the side plank Warrnambool style approach — calm, steady, and precise — teaches your body to stay responsive under fatigue, not rigid against it.

Think of your supporting muscles like a small team. Everyone’s clocked in, working together.

Then one or two clock off early — maybe your side or hip muscles fatigue — and the others have to cover the shift.

They can keep it up for a while, but eventually someone complains.

That complaint is the ache.

That moment — when a few muscles tire before the rest — is what researchers call an endurance gap.

It’s the quiet imbalance between muscles that should share the load.

When one area fades too early, another compensates — often your lower back.

It’s not about being unfit; it’s about your body running out of even effort.

Bracing, used strategically, is helpful.

McGill’s research shows that short, task-specific bracing increases spinal stiffness and tolerance to load when you need it — lifting, changing direction, resisting a jolt (McGill et al., 1999; Kavcic et al., 2004).

But that’s very different from staying braced all day. In standing studies, people who develop pain show excess co-contraction and reduced movement variability — they hold too still for too long (Gregory et al., 2008; Sorensen et al., 2015).

That rigidity feels protective but it costs endurance: fatigue builds, load sharing fades, and the back fills the endurance gap.

Your body relies on proprioceptors — tiny sensors in muscles and joints — to keep posture responsive.

When they’re active, they trigger subtle sway and automatic corrections that share effort evenly.

Lose that responsiveness through long static holds, and your spine starts micromanaging each adjustment (Callaghan et al., 2001).

So when you practise endurance, you’re not just getting “core strong.”

You’re training your body to listen — to stay tuned, to keep moving just enough.

True stability looks like this: quiet, steady, responsive.

📌 KEY TAKEAWAY:

Endurance is your body’s quiet stabiliser.

Strength helps you lift once — endurance helps you last all day. When fatigue sets in, small muscles clock off early and your back covers the shift. Train endurance, and you train your body to share the work evenly.

The 60-Second Side Plank Test

What if one simple test could show how well your body endures?

The side plank Warrnambool method focuses on control over strain. It’s less about maxing out time and more about how evenly your muscles share the effort.

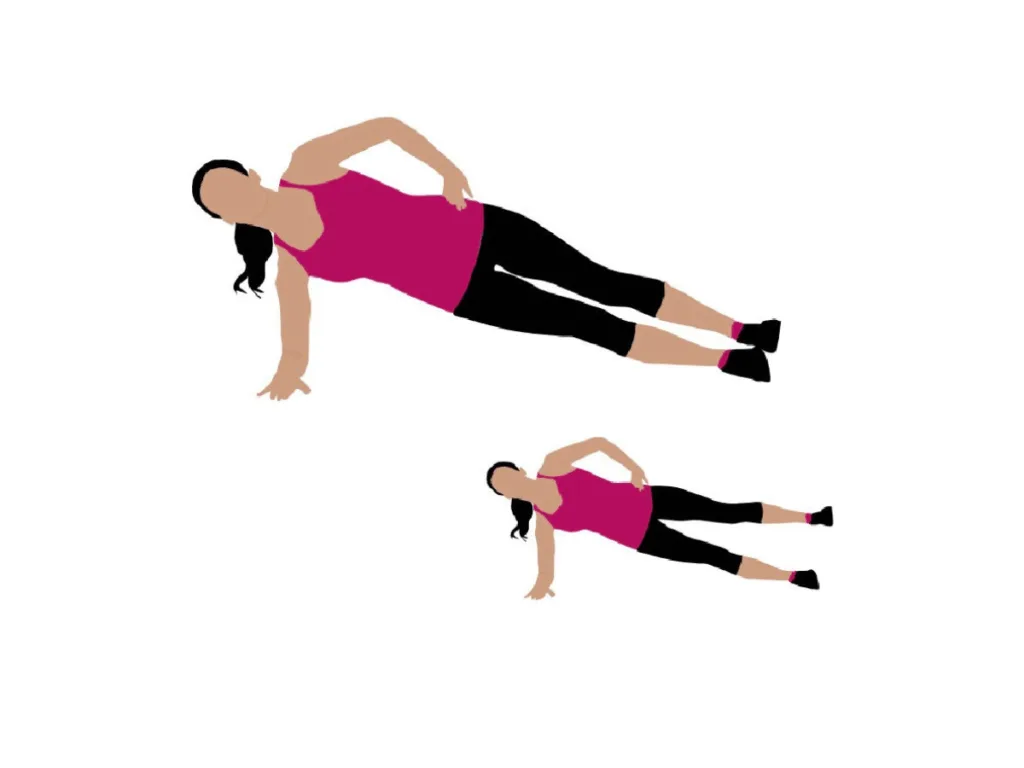

The side-plank (side-bridge) sits inside McGill’s Big-3 because it delivers high spinal stability with moderate compression (Kavcic et al., 2004).

It’s also a quick screen of whether your lateral trunk and hip stabilisers can keep up with daily life.

Try it:

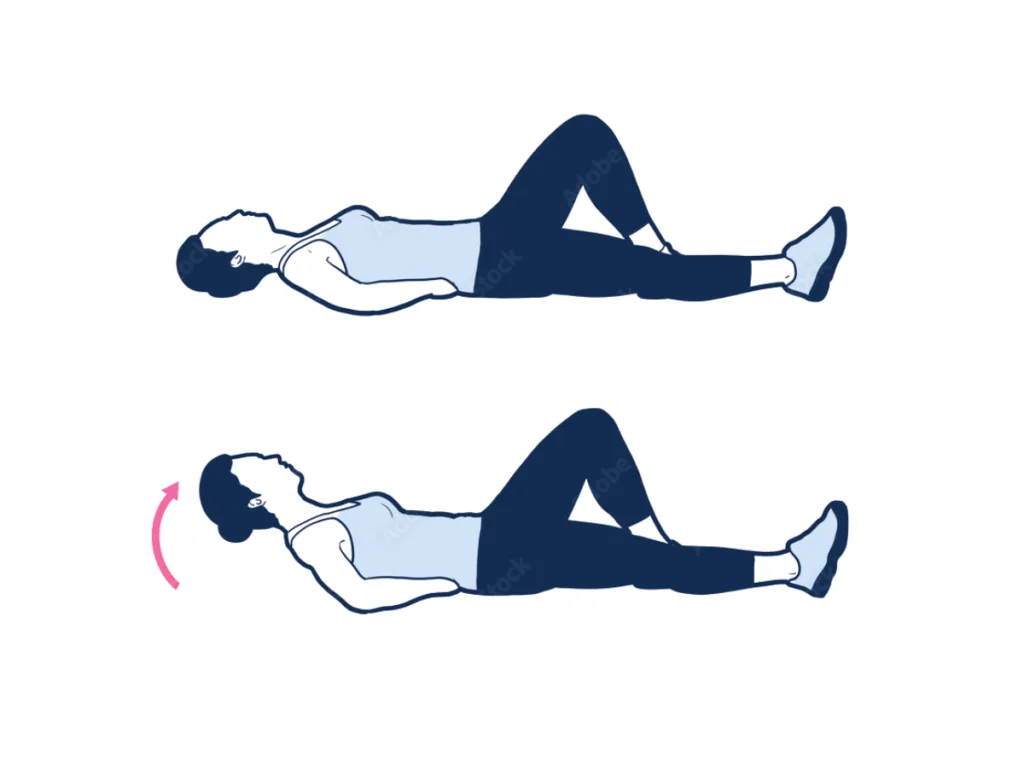

- Lie on your side, elbow under shoulder, legs stacked.

- Lift hips into a straight line from ankles to head.

- Breathe normally. Stop when hips sag or the top shoulder rolls forward. Repeat other side.

Benchmarks: Men ≈ 83 s | Women ≈ 64 s.

Anything below 60 s suggests an endurance gap — your lateral muscles are clocking off before your back does (McGill et al., 1999; Marshall et al., 2011).

The goal isn’t to chase time — it’s to restore even effort so every muscle does its share.

For a deeper look at our full approach, explore our

Holistic Osteopathy for Wellness for details on holistic osteopathic assessment and care.

The McGill Big-3: Why These Three?

Think of the Big-3 as a stability circuit — each drill strengthens a different line of support with minimal spinal load:

- Modified Curl-Up → front-line endurance without flexion stress.

- Side-Plank → lateral chain stability.

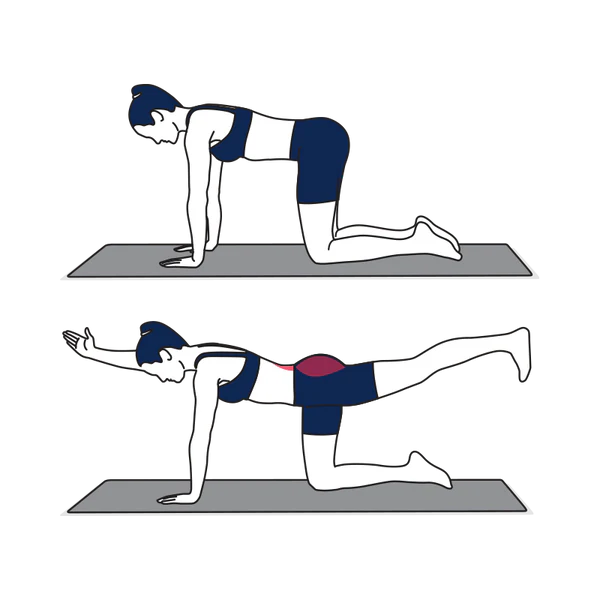

- Bird-Dog → posterior and cross-body control for whole-system coordination.

Together they train your body to share effort in every direction, preventing the spine from doing all the work (Kavcic et al., 2004).

Movement as Medicine

Ever notice how standing still feels harder than walking?

Movement keeps stabilisers switching on and off — the body’s version of rest and reset.

Even small posture changes — shifting your weight or bending a knee — help prevent fatigue. The side plank Warrnambool approach builds that same awareness, reminding your body how to stay active without overworking your spine.

In studies, people who allowed small movements during prolonged standing reported less pain (Viggiani & Callaghan, 2016).

Fatigue forced them to fidget — and that fidgeting reduced strain.

You’ve felt it when you rest a foot on a rail or shift your stance at the sink.

Each change redistributes pressure, gives certain muscles a breather, and refreshes blood flow.

Small moves, big difference:

- Alternate weight between legs.

- Rest one foot on a step.

- Roll ankles or bend a knee while chatting.

- Place a small object under one foot, then swap.

These micro-adjustments mimic the movement variability of people who don’t develop pain — proof that movement protects posture.

📌 KEY TAKEAWAY:

Simple at-home tests can help you spot tight hips—before your back starts to pay the price. Improving hip mobility makes almost every movement safer and easier for your spine.

Building Endurance & Resilience: Your Training Plan

Adding the side plank Warrnambool routine to your daily reset helps rebuild core balance without overloading your spine — five calm minutes a day is enough.

Picture this: you finish a long day, normally stiff.

Tonight you try something different — five calm minutes of deliberate work.

1. Assess your baseline — Do the side-plank on each side. Note the times.

2. Sets, not strain — 4 × 30-second holds per side with 30-second rests.

3. Built-in resets — Between sets, march, rock heel-to-toe, or do wall pelvic tilts.

4. Progress gradually — Add 5–10 seconds per week or a fifth set.

5. Complete the circuit — Add curl-ups and bird-dogs on alternate days.

6. Quality beats quantity — Stop when alignment drifts; poor form teaches poor patterns.

7. Integrate it — Use small movements at work, set a 2-hour reminder to reset posture.

Short, consistent practice rebuilds the kind of endurance your back can trust for decades.

When to Seek Guidance

If you notice sharp pain, tingling, or persistent tightness, it’s worth an assessment.

A registered Warrnambool osteopath can evaluate how your hips, spine, and daily movement habits interact, and design a plan that fits your lifestyle.

At The Barefoot Osteo, every treatment starts from the ground up — restoring mobility, stability, and balance so movement feels natural again.

📌 KEY TAKEAWAY:

Listen when your body asks for help.

If pain, tingling, or tightness keeps showing up, it’s a sign your movement system needs support. A registered Warrnambool osteopath can assess how your hips, spine, and habits interact — and help you move with confidence again.

Find more tailored routines and daily strategies in our Chronic Lower Back Pain cornerstone blog

FAQs: The 60-Second Fix

A: It’s a research-based, 30-day side-plank protocol designed to build endurance in your core and hips — the muscles that stabilise your spine.

A: The side-plank trains endurance in the lateral chain — hips and obliques — so your back doesn’t carry the load alone.

A: Anyone who feels stiff after standing or has recurring back fatigue. It’s safe for most people and can be adapted under guidance from a registered osteopath.

A: You’ll find the full 30-day guide and downloadable ebook in our upcoming release 👉 The 60-Second Fix: A 30-Day Side Plank Protocol to Bulletproof Your Core. Or follow the link to book an assessment today 👉 BOOK APPOINTMENT

📌 KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Endurance beats strength.

- Pain doesn’t show up when you’re strong — it shows up when you’re tired. Building endurance in your core and hips keeps your back stable long after strength fades.

- The side-plank is your early warning system.

- If you can’t hold 60 seconds, you may have an endurance gap — meaning your hips and sides fatigue before your back, forcing it to do extra work.

- Small moves protect big structures.

- Gentle postural shifts — a foot on a rail, a knee bend, a weight change — restore blood flow and reduce spinal fatigue. Movement protects posture.

- Smart consistency wins.

- Five calm minutes a day with the McGill Big-3 builds quiet, lasting stability. Quality reps and regular resets beat occasional hard sessions every time.

Conclusion — Closing the Loop on That Coffee Line

Back to the café queue.

You feel that same slow pull across your lower back — only now, you recognise it.

It’s not weakness; it’s feedback.

Research shows that people who develop transient pain during standing are more likely to face low-back pain later (Nelson-Wong & Callaghan, 2014; Viggiani & Callaghan, 2018).

But that story can change.

By integrating the side plank Warrnambool approach into your week, you retrain endurance, restore rhythm, and move with confidence again — that’s the Barefoot Difference.

When you rebuild endurance, reintroduce small movements, and train your Big-3, you share the work again.

The result? A back that adapts instead of aches.

Next time that ache appears, shift your stance, breathe, re-centre — then finish your day knowing you’re teaching your body to move smarter.

Experience the Barefoot Difference — working from the ground up to keep you steady, mobile, and pain-free.

References

Callaghan, J. P., Salewytsch, A. J., & Andrews, D. M. (2001). An evaluation of predictive methods for estimating cumulative spinal loading. Ergonomics, 44(9), 825–837.

Fewster, K. M., Gallagher, K. M., & Callaghan, J. P. (2017). The effect of standing interventions on acute low-back postures and muscle activation patterns. Applied ergonomics, 58, 281–286.

Gallagher, K. M., & Callaghan, J. P. (2016). Standing on a declining surface reduces transient prolonged standing induced low back pain development. Applied ergonomics, 56, 76–83.

Gregory, D. E., & Callaghan, J. P. (2008). Prolonged standing as a precursor for the development of low back discomfort: An investigation of possible mechanisms. Gait & Posture, 28(1), 86–92.

Kavcic, N., Grenier, S., & McGill, S. M. (2004). Quantifying tissue loads and spine stability while performing common stabilization exercises. Spine, 29(20), 2319–2329.

Marshall, P. W., Patel, H., & Callaghan, J. P. (2011). Gluteus medius strength, endurance, and co-activation in the development of low back pain during prolonged standing. Human movement science, 30(1), 63–73.

McGill, S. M., Childs, A., & Liebenson, C. (1999). Endurance times for low-back stabilization exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(8), 941–944.

Nelson-Wong, E., & Callaghan, J. P. (2014). Transient low back pain development during standing predicts future clinical low back pain in previously asymptomatic individuals. Spine, 39(6), E379–E383.

Sorensen, C. J., Johnson, M. B., Callaghan, J. P., George, S. Z., & Van Dillen, L. R. (2015). Validity of a Paradigm for Low Back Pain Symptom Development During Prolonged Standing. The Clinical journal of pain, 31(7), 652–659.

Viggiani, D., & Callaghan, J. P. (2018). Hip Abductor Fatigability and Recovery Are Related to the Development of Low Back Pain During Prolonged Standing. Journal of applied biomechanics, 34(1), 39–46.